What do the following titles have in common: Ulysses, Animal Farm, The Great Gatsby, The Catcher in the Rye, Mrs. Dalloway, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn?

If you answered that they’ve all been banned or challenged in the United States at some point, give yourself a gold star. Each is now considered a literary classic, yet each has faced calls for removal from classrooms or libraries due to language, political themes, or perceived moral threats.

Now, Danvers is facing its own chapter in that long national story.

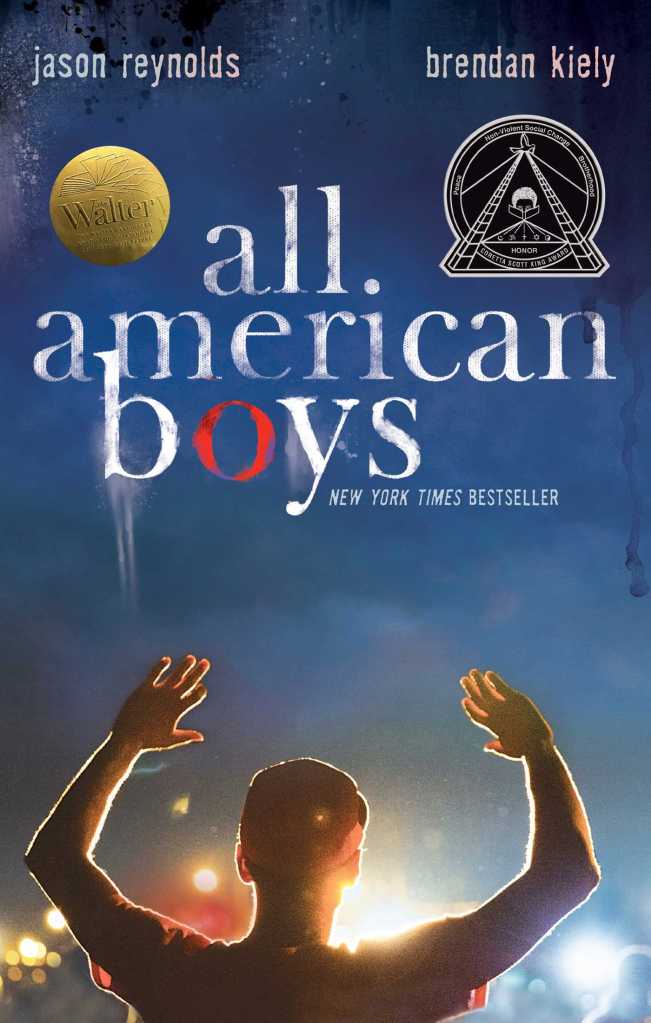

A recent complaint from a parent brought All American Boys, a 2015 young adult novel by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely, under scrutiny. The book is currently being read by eighth-grade students in Danvers. The parent objected to the use of profanity and depictions of underage drinking and substance use, expressing concern that the material is not appropriate for students at that age.

While the novel does include harsh language and difficult themes, these are used to serve its larger message: to explore systemic racism and police brutality through the eyes of two teens, one Black, one white, who witness and experience violence at the hands of law enforcement. The story challenges both characters, and by extension, the reader, to examine bias, privilege, and moral responsibility.

It’s important to note that All American Boys has not been banned in Danvers. The district clarified that students were given the option to opt out, and only about 5 percent of eighth graders chose to do so.

Still, the pushback raises important questions: Should books that depict real-world injustices and uncomfortable truths be avoided in middle school? Or is that precisely where they belong?

Let’s be honest—eighth-grade students today are not strangers to strong language or awareness of drinking. Shielding them from fictional accounts of issues that exist in the real world doesn’t prepare them to engage with it critically; it leaves them ill-equipped. And when we avoid confronting racism, we risk allowing silence to reinforce it.

Consider The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, another frequently challenged book. Yes, it repeatedly uses the n-word. But Twain’s portrayal of Huck’s evolving friendship with the enslaved Jim is a powerful indictment of slavery and racism. Twain forces readers to reckon with it. That is literature doing its job.

That same lens can, and should, be applied to All American Boys.

Kudos to the Danvers Teachers Association for standing up for the novel’s educational value. In a statement, the union defended the book’s inclusion, emphasizing the importance of “teaching from a place of truth” and encouraging critical thinking on social justice issues. Removing such content from classrooms not only narrows students’ perspectives but it undermines the very purpose of education.

If we want young people to be thoughtful citizens in a complex world, we must trust them enough to engage with that complexity in the classroom.

Leave a comment